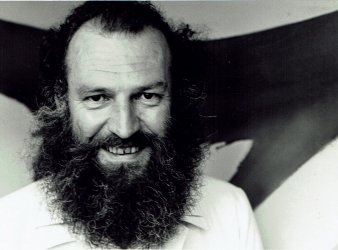

Sebastian Black, who will be remembered with affection by colleagues and with admiration by generations of former students, has died aged 77. The son of George Black, a distinguished British eye-surgeon, and his Cuban-American wife, Stella Harding, Sebastian was born in Leeds, Yorkshire in 1937. Educated at Rugby, and Oxford, before completing a degree at the University of Leeds, he was appointed to a Lectureship in English at the University of Auckland in 1966. Sebastian taught in the English Department for thirty-four years, serving as Deputy HOD for some while until his retirement in 2000. He had been in poor health since the death in 2011 of his partner, the historian Dame Judith Binney, with whom he lived for 40 years.

This bald summary does scant justice to an exceptionally colourful personality. Perhaps as a consequence of his birth on the disorderly festival of All Fools, Sebastian was always suspicious of authority, even in its more benign guises, and his life was punctuated by episodes of rebellion. At the age of 13 he ran away from Wennington Hall School, the progressive, A.S. Neill-influenced establishment chosen by his father, and opted for the more conventional public school discipline of Rugby. Here, however, in his final year, he would persuade his fellow-prefects to defy the tradition of four hundred years by suspending the practice of corporal punishment. At Oxford, overcome by romantic disappointment, he turned his back on the academy and impulsively took flight to France, where he joined the French Foreign Legion. Posted to the Legion’s headquarters at Sidi Bel Abbès, he found himself embroiled in the colonisers’ bitter war against Algerian independence. Whatever his ideological reservations about this conflict, Sebastian’s strong sense of principle compelled him to serve out the five-year term to which he was committed, despite his being severely wounded towards the end of his time. He rose to the rank of sergeant; and such was his outstanding record that his superiors tried to persuade him to enter officer training – an honour normally reserved for French citizens. By now, however, Sebastian was in no doubt that he had been on the wrong side in what would prove to be a defining anti-colonial struggle; and that conviction would have a shaping influence on his understanding of the world, and on his future approach to literature.

After leaving the Legion, Sebastian went to read English at the University of Leeds, where his critical thinking – already influenced by his left-leaning father -- would be moulded by the charismatic teaching of the Marxist Arnold Kettle. It was Kettle who taught him to recognise the intimate relationship between literature and politics: ‘Art for art’s sake,’ Sebastian would become fond of quoting Chinua Achebe, ‘is just so much deodorised dogshit’. It was this belief that would later compel him, in the teeth of opposition from more conservative colleagues, to establish New Zealand’s first course in post-colonial fiction; and it was no accident, of course, that Frantz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth -- which grew out of Fanon’s experience in the Algerian resistance – should have become a cornerstone of his teaching in the course.

When Sebastian first arrived in Auckland, however, his energies were necessarily absorbed in more orthodox parts of the discipline, since (like all staff at that time) he was required to teach across the entire field of English literature, from Shakespeare to the twentieth century – a challenge he answered with characteristic élan. Before long, though, he would establish a particular expertise in twentieth-century fiction and drama; and his shameless flair for the dramatic made him a wildly popular lecturer, not least with the large first-year classes whom he introduced to the difficult writing of Samuel Becket, Harold Pinter, Edward Bond, John Arden and others: his virtuoso lectures on Endgame, for which he would emerge, like Beckett’s Nag and Nell, from a filthy-looking dustbin, became a legendary attraction.

A passionately committed teacher who believed that the first responsibility of academic staff was to their students, Sebastian invariably shouldered one of the Department’s heaviest teaching loads -- even when, towards the end of his career, he became Deputy Head of the English Department and chose to accept the greater part of its routine administrative responsibilities. At the same time Sebastian’s political commitment ensured that he remained an energetic member of the staff union throughout his career, and in the 1970s he helped to set up the Lecturers’ Association to advance the interests of junior staff. Throughout the seventies and eighties he worked hard to bring about an extensive democratisation of the university’s administrative structures, helping to gain staff and student representation at both faculty and university level; and he himself became an outspoken staff representative on the University Council, serving on a number of its key committees. Here his mastery of standing orders (equalled only by his command of the minutiae of cricketing history) regularly gravelled his opponents.

Sebastian’s energies were by no means confined to the academic world, however. His drama teaching was complemented and underpinned by an extensive involvement in live theatre: he worked as a dramaturg with a number of young playwrights in both Auckland and Wellington, he served for several years as a board member for the Mercury Theatre, and acted as the Listener’s main Auckland theatre reviewer for much of the seventies and eighties. Beyond the university he was engaged in a succession of radical causes: his opposition to the Vietnam war saw him narrowly evade arrest in demonstrations against the visit of the United States Vice-President, Spiro Agnew, at the Intercontinental Hotel in 1970; in the 1980s he regularly took part in harbour demonstrations against the presence of American nuclear ships; and in 1981 he was prominent in the struggle against the Springbok tour, undergoing arrest with a number of colleagues (including Karl Stead and Roger Nicholson) during the successful disruption of the Hamilton game early in the tour. In 1995 he and Judith Binney, inspired by an earlier canoe trip down the Whanganui River with protest leader Niko Tangaroa, would travel to join the protestors at Pākaitore (Moutua Gardens) in Whanganui.

Sebastian and Judith’s involvement in that struggle was, of course, closely bound up with her emergence as perhaps the country’s most distinguished scholar of Māori history—a turn in her career that began when she, Sebastian, and a small group of friends walked into the Urewera in 1976 to visit the prophet Rua Kenana’s old settlement at Maungapōhatu. Mihaia, Judith’s study of Rua, written with Gillian Chaplin and Craig Wallace, appeared three years later; and from that point on Sebastian would act as her informal editor, helping to bring to publication the magnificent series of books that culminated in Encircled Lands (2009). In Judith’s last few years, Sebastian’s unfailing love and support helped to carry her through the succession of illnesses that led up to her death in 2011. His selfless neglect of his own health in this period, combined with his grief at losing Judith, meant that Sebastian was never really well again. But those who knew him will never forget his continuing devotion to Judith’s mother, Marjorie Musgrove, nor the courage and wonderful good humour with which he faced his long last illness. An old friend recently described Sebastian as ‘vehement’: this was a nicely chosen euphemism - like many of us, he could at times be a difficult and obstinate man; but his generosity and capacity for friendship were unequalled.

He is survived by his dear brother Edward, his beloved sisters, Caroline Wright and Margarita McGowan, and his adoring nephews and nieces.